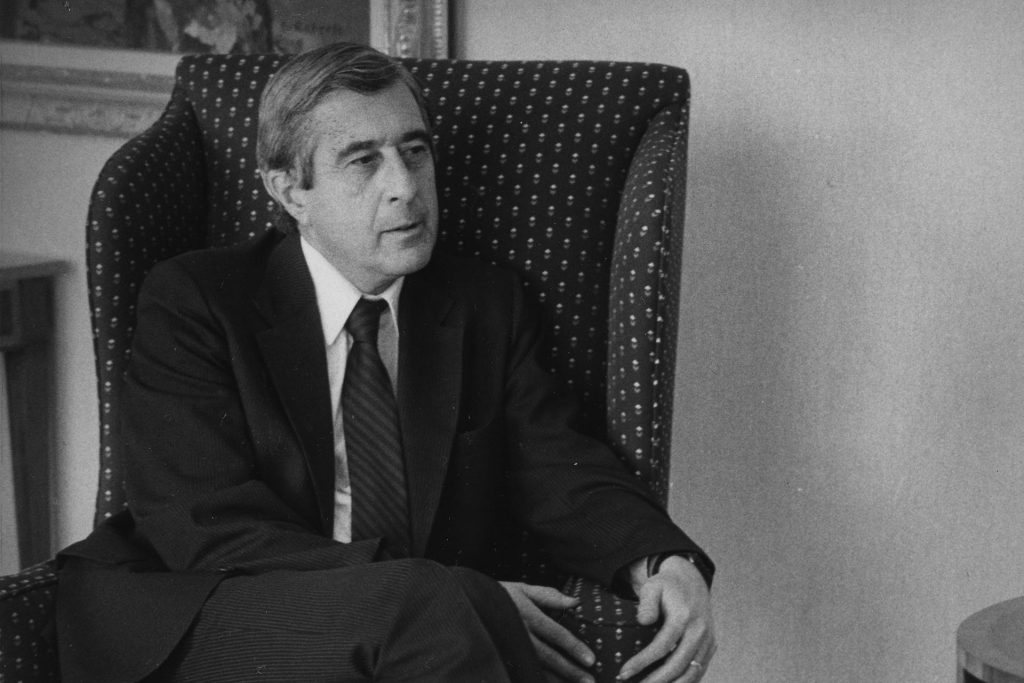

Donald McIvor, who has died of COVID-19 at the age of 91, was chairman and chief executive officer of Imperial Oil at a time when the Canadian subsidiary of Exxon clashed with Pierre Trudeau’s Liberal government over the National Energy Program, introduced in 1980.

As the head of Canada’s largest integrated oil company, Mr. McIvor was a vocal critic of the National Energy Program, which was designed to promote Canadian ownership of the energy industry and oil self-sufficiency. Most oil executives saw it as the attempted nationalization of the country’s oil industry, but Mr. McIvor was a diplomat who, no matter what he felt, knew he had to deal with the people in power in Ottawa.

Though Imperial Oil was 70-per-cent owned by Exxon (known as Exxon-Mobil since 1999) of New York, in an interview with The New York Times in December 1981, Mr. McIvor emphasized he was a Canadian.

“Like virtually all Canadians, I totally support the major objective of the federal government’s energy program, which is the achievement of domestic oil self-sufficiency,” Mr. McIvor said just weeks before he became chairman and CEO of Imperial Oil. But as the head of the largest foreign-controlled oil company, he objected to the purchase of another foreign oil giant, Petrofina, by the state-owned Petro-Canada.

“[It] represents a transfer of $1.5-billion, much of it a loss to Canada, without any contribution to the goal of self-sufficiency.”

In one speech, Mr. McIvor used the phrase “triple whammy” to describe what he saw as the three big problems of the sharp recession of the early 1980s: record-high interest rates and falling oil prices compounded by the National Energy Policy. “The triple-whammy comment got picked up in the press far and wide because it really captured the essence of the industry,” said his main speechwriter at the time, Brian Hay.

To make its policy more palatable, the federal government introduced a national oil price, lower than the world price, which Mr. McIvor and Imperial Oil criticized. It led to the unintended consequence of Americans driving north to buy cheap Canadian gasoline, including truckers who would reroute to take Canadian highways.

The policy also hit Imperial Oil’s profits: In 1982, the year Mr. McIvor took over as chairman and CEO of Imperial Oil, its earnings fell 43 percent.

“We had very little idea what the future held,” he told The New York Times in 1984.

In fact, after some initial grumbling, Mr. McIvor played nice with the federal government during his first two years on the job. This approach paid off, according to a lengthy 1984 New York Times piece. “[Imperial Oil] has cleverly turned the Government’s ‘Canadianization’ policy to its own advantage by forming partnerships with Canadian companies eligible for big subsidies.”

The man behind the strategy was the Canadian running the foreign-owned oil giant: Mr. McIvor.

Donald Kenneth McIvor was born on April 12, 1928, in Winnipeg, where his father was a well-known columnist for the Winnipeg Free Press. According to Donald’s son Gordon McIvor, the McIvor family’s roots in Canada went back to the 18th century, when a McIvor ancestor joined Alexander Mackenzie on his voyage of discovery, the first Europeans to cross the continent to the Pacific Ocean, a dozen years before the Americans Lewis and Clark.

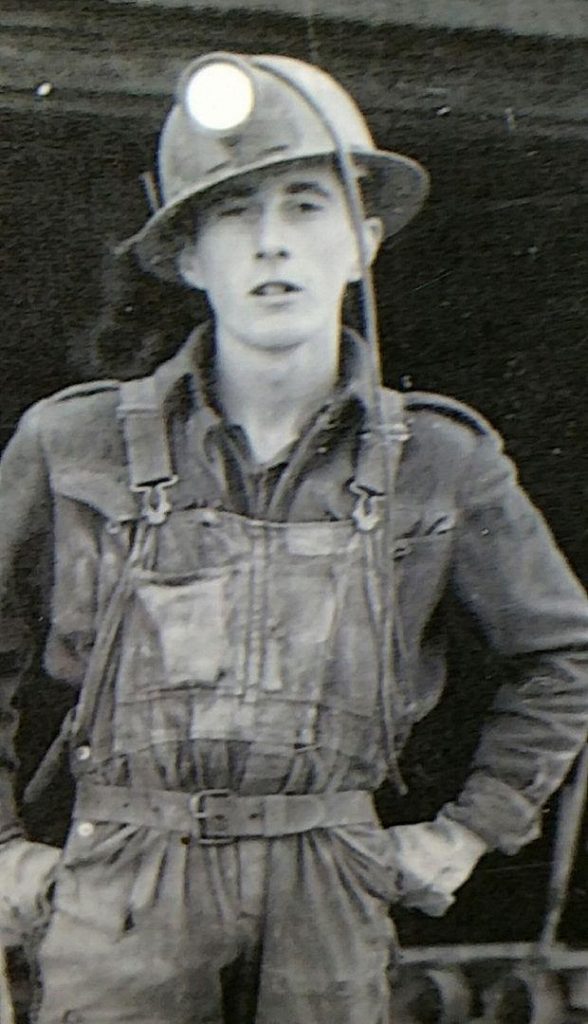

Donald McIvor, the future CEO of Imperial Oil, working at a summer job as a miner at 16.

COURTESY OF THE FAMILY

Growing up, he was known as Donny Why, because he was so curious and always asking questions. His parents divorced when he was still at school, and he was raised by his mother, Nellie Rutherford. When he was 16, he spent the summer working in a gold mine, providing much-needed income for his mother and sister, Moira. He went to the University of Manitoba and graduated with an honors degree in geology. His first full-time job was with Imperial Oil in 1950, and he stayed with the company for more than 40 years. The first part of his career was spent finding oil and gas deposits, working out of Calgary.

“He was one of the leading Canadian earth scientists of his day, discovering major oil and natural gas reserves in Western Canada throughout the 1950s and 1960s,” his son Gordon McIvor said. After many years of working in the field, he was approached to become a manager for Imperial Oil. He resisted, as he outlined in one of his two autobiographical books, in a chapter titled “A Reluctant Executive.”

“My ambition was to be the best practical earth scientist the company had ever had. I had a very low opinion of managers, executives, and administrators. I thought of them as ‘suits’ who occupied themselves at arcane, largely pointless tasks that made life complicated for truly productive persons such as myself,” Mr. McIvor wrote.

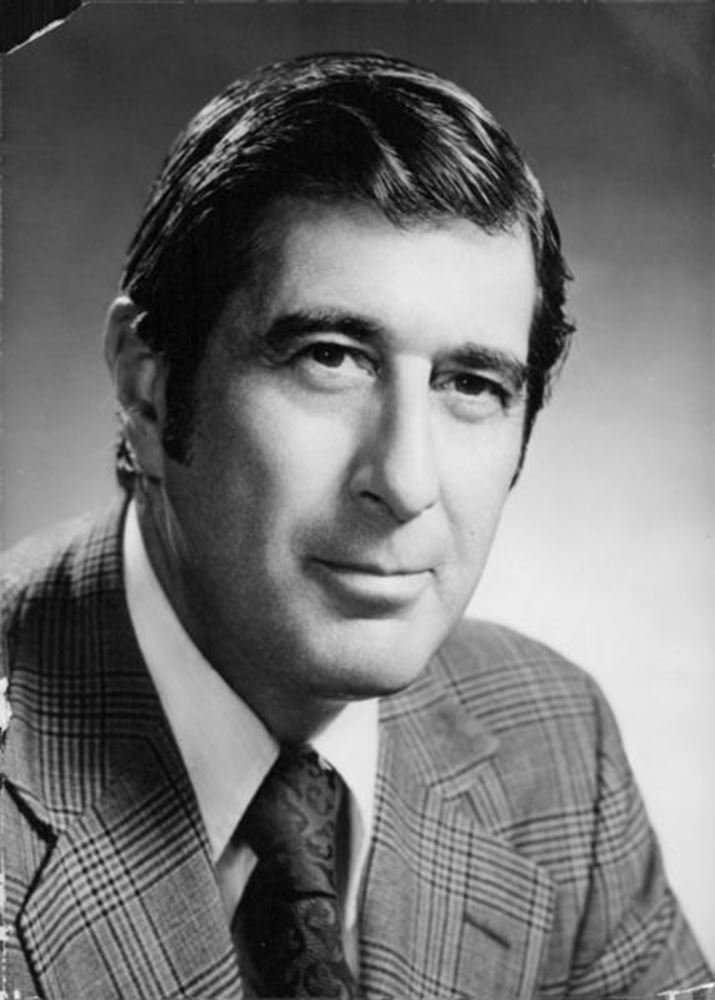

He accepted the job and rose quickly through the corporate ranks. At one point, he was put in charge of all exploration for the parent company, Exxon, before moving back to Canada as senior vice-president at Imperial Oil. He then landed the top job in Canada, looking out over a 19th-century cemetery and the Toronto skyline from his penthouse office at Imperial Oil headquarters on St. Clair Avenue.

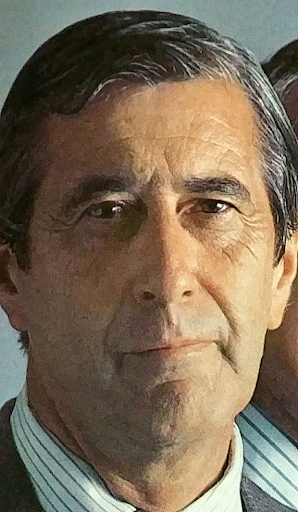

As one of the most powerful people in corporate Canada in his day, Mr. McIvor was the subject of many profiles. Journalist and author Peter Foster wrote about him in a piece for Saturday Night magazine and a 1982 book, The Sorcerer’s Apprentices: Canada’s Super-Bureaucrats and the Energy Mess.

“McIvor is a good-looking man with a firm set to his jaw. His delivery has a little bit of Gary Cooper’s honest deliberation, a touch of Jimmy Stewart’s sincere hesitation,” Mr. Foster wrote in his book. “Although he sometimes comes across as Mr. Deeds newly arrived in Washington, it’s well to remember that he is a corporate astronaut.”

Though that profile spoke of movie-star looks, Mr. McIvor was the antithesis of the Hollywood image of a brash oil executive. The people he worked with remember that he never raised his voice or used foul language.

“Don was a very thoughtful, analytic man, not bombastic. I never saw him get argumentative or loud and never heard him raise his voice. He was assertive in a quiet and disciplined way. But he had a wry sense of humor, and he’d use it if he wanted to criticize you,” Mr. Hay said.

After three years as head of Imperial Oil, he was promoted again, this time to senior vice-president at Exxon headquarters in New York. He was also on the oil giant’s board of directors and other boards, including the Royal Bank of Canada.

He retired in 1993, when he reached the mandatory retirement age of 65, but stayed active on other boards. Throughout his long life, Mr. McIvor remained a curious person. When he ran Imperial Oil, he had lunches with people outside the oil industry and Bay Street, so he didn’t become too isolated.

“He would have lunch with authors … and then the next week he would have lunch with the leader of the United Way of Toronto,” his son Gordon said. “Every week, he set out to widen his horizon and try to understand what other people were thinking about things outside the energy industry.”

He also loved to read.

“Don read everything he could and no matter what question you asked him, he always made sure he gave you the best answer so that you understood it. … He loved sharing his knowledge,” his wife, Debbie McIvor, said.

Mr. McIvor died on March 29, after contracting COVID-19 while living at a seniors residence in Norwalk, Conn. He was 91, two weeks and a day shy of his 92nd birthday. He had five children with his first wife Avonia Isabelle, who predeceased him in 2015. He leaves his wife Debbie; children Gordon, Donald, Daniel, and Debbie; and stepchildren Richard, Elizabeth, and Ashley. His son Duncan died in 2015.